Excerpts

Getaway Day

"Fathers and Sons"

– Jewish Proverb

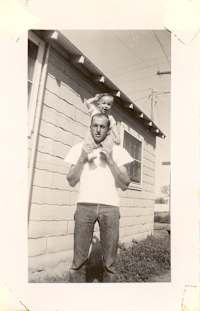

It’s complicated. Fathers and sons are. It’s been said that it’s up to the son to live up to his father’s reputation, or atone for his mistakes. Unfortunately, that’s something we never can win. As sons, we are shaped by the tug of our father’s expectations and the weight of his disappointments. We will always dwell in his shadow.

Fathers and sons have been rivals since forever. They have long competed for the respect of their community, the praise of their peers, and the love of their wife/mother. And, they’ve always had issues. Their conflict is as old as time, stretching back to bc and The Bible, before and beyond. Like Abraham and Isaac, or the Prodigal Son, the Good Book is full of stories about battles between men and their boys. As are myths, fables, and fiction, which tell more vivid tales of their clashes and struggles: Telemachus and Odysseus, Oedipus and Laius, the Hamlets, Geppetto and Pinocchio, George Bailey and Zuzu, Atticus Finch and Jem, Ozzie and Ricky, Mr. Cleaver and the Beaver. It’s really nothing new. It’s always been a kind of Greek tragedy. There were some times I hated my father, and other times I loved him. Some times I took his advice, other times I ignored it. Some times I wished he wasn’t around, other times I feared my wish might come true.

For Baby Boomers who grew up when I did, it was up to the father to teach his son to be a man, to be tough in a cold, hard, unforgiving world. It was up to the mother to dress the wounds when that world kicked your butt. It was up to the father to provide qualified approval. It was up to the mother to provide unconditional love. It was up to the father to run alongside as you tried to ride your bike for the first time and shout encouragement as you did. It was up to the mother to stand on the sideline frightened you’d fall, and wipe away the tears when you did.

Fathers took charge. Mothers took care. Between them, with a little help from family and friends, community and society, a baby boy would grow up to be a man – a normal, productive, well-balanced, and committed member of society. In the case of Baby Boomer boys like me, that meant being self-assured, self-absorbed, and self-conscious about changing the world and making things right, and filled with a sense of entitlement and great expectations for our own success.

Many believe a boy’s struggles with his father make him a man. I never struggled with my father. That’s because he, like many of the men of his generation and unlike the men of his father’s generation, didn’t feel the need to teach his children how to make it in a tough world because he believed his kids weren’t going to live in the same world he had. It was bound to be better. My father and I didn’t always agree. We didn’t always see the world the same way. And we didn’t always make the same choices. But, on the important issues – like family and the right thing to do, community and how you treated people, friends and taking care of each other, values and conformity for the common good, and duty – we were as one.

Sports offered one of the best ways (sometimes the only way) a father could get close to his son. By listening to, reading about, or watching the game together, by teaching the game and perhaps coaching it, by keeping score and debating the strengths and weaknesses of your idols, the two of you could spend time alone together and learn to at least respect, certainly enjoy and appreciate, even like or love, one another.

Baseball, in particular, was a game that bound together fathers and sons. Like so many things, baseball was easy and it was hard. It was graceful and clumsy, quirky and predictable, fair and foul, old and new, wild and controlled, relaxed and intense, fun and torture. Often thanks to the expectations. That you enjoyed it. That you were good enough. That you’d want to play it again. With him. That he’d have time for you now and you’d have time for him later. Baseball, in all its elegant and simple complexity, echoed the saga of fathers and sons, as well as the unbroken circle of life.

Baseball was the only sport for me; probably because summer was my favorite season. Maybe, because it was familiar. I understood it. I got it. And I could play it. There was something about the history and tradition, innocence and nostalgia, the symmetry and sense of fair play, the rite and ritual. Throwing, catching, hitting, running, and sliding all seemed so natural and effortless. It always made me think of a time when things seemed easier and better. I liked the fact that it was the player that scored, not the ball. That it included errors, since we all made them. That it valued a keen eye, quick reflexes, and good judgment. That it was a team game. That it wasn’t played against the clock. That, as writer Roger Angell once wrote, “Since baseball time is measured only in outs, all you have to do…is keep hitting, keep the rally alive, and you have defeated time. You remain young forever.” For me, baseball was the never-ending game. And, it felt like home.

"Opening Day"

– Lou Boudreau, American League Player and Manager

Opening Day always meant the end of winter and the beginning of summer (although it was really spring). The last of the season I hated and the first of the season I loved. Every true baseball fan couldn’t wait for that special day. We’d all been marking off our calendars since the last pitch of last year’s World Series. On Opening Day, we could live and breathe and hope again. On Opening Day, every team was in the race. Everyone was a contender.

As the first official franchise in Major League Baseball history, the Cincinnati Reds always got to be the first team to play on Opening Day. They held the “opening of the Openers.” It was said that the citizens of the “Queen City” looked upon Opening Day as “one small notch below Christmas.”

Since baseball was, after all, the national pastime, Opening Day always seemed to attract politicians anxious to show the American people they were one of them, had the right stuff, and could wing a fast ball up there with the best of them. President William Howard Taft, who was a big fan – in size and enthusiasm – was the first president to throw out the first pitch way back on April 14, 1910. In 1950, Harry S. Truman, who happened to be ambidextrous, threw out balls both right-handed and left-handed. On April 9, 1962, President John F. Kennedy continued the tradition by throwing out the first pitch at Washington’s new District of Columbia Stadium.

Early Wynn, a Hall of Fame pitcher who played his entire career in the American League for the Senators, Indians, and White Sox, once said about Opening Day, “An opener is not like any other game. There’s that little extra excitement, a faster beating of the heart. You have that anxiety to get off to a good start, for yourself and for the team. You know that when you win the first one, you can’t lose ‘em all.” I liked his name and his optimism.

Opening Day for the Yankees that year was at two o’clock EST on April 10 against the Baltimore Orioles at Yankee Stadium. Mrs. Claire Ruth, Babe Ruth’s widow, threw out the first pitch. My dad and I were listening in. Since he worked for the phone company, Dad could pull a few strings for important things. He made a few calls to some of his service buddies who worked for the New York Telephone Company. They set up a temporary phone line so my dad could listen to the game long-distance. It was a direct line from Yankee Stadium to our little house in Modesto. He’d connected the phone line to a tiny amplifier and speaker, so we could both listen. That’s how much my dad loved his Yankees. He felt bad about doing it, but only until the first pitch. He always took the day off work and let me stay home from school. We couldn’t afford to go to the real thing, so we did the next best thing.

"Hero"

I missed him every day.

Mickey Mantle was my other hero. He won his third, and last, American League Most Valuable Player award that year. Tom Tresh was named AL Rookie of the Year, while Ken Hubbs of the Cubs won the NL award. Maury Wills just beat out Willie Mays for the MVP in the NL. Dodger Don Drysdale edged out Jack Sanford and Billy Pierce of the Giants for the Cy Young Award. Elroy Face of the Pirates and Dick Radatz of the Red Sox won The Sporting News Fireman’s Trophies for the top relievers in each league. Mantle, Richardson, and Terry of the Yankees won Gold Gloves, as did Mays and Jimmie Davenport of the Giants.

In an interview with The Sporting News after the season, Ralph Houk was asked, if he had a choice of centerfielders, who would he pick, Mays or Mantle? “There is nobody alive better than Mantle,” said Houk. “I’ve seen him do too many things. I’d just as soon have him run as Maury Wills. When you need a base stolen, Mantle will steal it. He doesn’t steal as many but, when he goes, he makes it.”

Mantle finished the year with eighty-nine RBIs and thirty home runs in 123 games. He led the American League in on-base percentage (.486) and slugging percentage (.605). He finished second in the league in batting with an average of .323. He turned thirty-two during the 1962 season. He had a good year and the fans loved him. It was that year that Mantle may have begun to realize that his best days might be behind him. Maybe that’s why he was such a fan of the Willie Nelson country song that said, “Today’s gonna make a wonderful yesterday.”

Mantle would play his entire eighteen-year Major League Baseball career for the New York Yankees as an outfielder and first baseman. He won three American League MVP titles and played in twenty All-Star games. He won the Triple Crown in 1956. Mantle appeared in twelve World Series, winning seven of them. He still holds the records for most World Series home runs (18), RBIs (40), runs (42), walks (43), extra base hits (26), and total bases (123). He is also the career leader in game-ending home runs, with a combined thirteen: twelve in the regular season and one in the postseason. He is considered one of the greatest players in baseball history and perhaps the greatest switch-hitter of all time. Mantle was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility in 1974, along with teammate Whitey Ford. Mantle retired in the spring of 1969, following the 1968 season, at thirty-seven. He didn’t die before he was forty, like the rest of his family and like he thought he was destined to. He died in 1995, after battling liver cancer. He admitted that his lifestyle had hurt his family and his game. “I’m not gonna be cheated,” he would say. As the years passed and he put forty in his rear-view mirror, he would often repeat a phrase his friend and Dallas neighbor, football great Bobby Layne, used to use: “If I’d known I was gonna live this long, I’d have taken a lot better care of myself.” Mantle asked his friend, country singer Roy Clarke, to sing “Yesterday When I Was Young” at his funeral because Mickey thought it summed up his life pretty well. Mantle’s epitaph read simply, “A great teammate.” In 2006, the U.S. Postal Service issued a Mickey Mantle stamp.

In 1962, I learned what it meant to be selfless, to think about others before myself, and to not be afraid of the unknown. I realized that I couldn’t control everything in my life, that stuff happens and nothing ever goes as planned. Most importantly, I discovered that expectations weren’t real, loneliness was absolute, change was inevitable, and laughter was essential. I became a believer in the power of positive thinking.

Mickey Mantle became, and remains, my favorite baseball player of all time.

Brighter Day

"Camp 4"

The sun was dropping as I pulled into the lot across from the dusty and boulder-speckled Camp 4, which was located a little east of Yosemite Village at the foot of Yosemite Falls. I found a secluded spot beneath a pine tree, unrolled my foam mat, spread out my bag, and opened it to air out. It hadn't been used in some time. Camp 4 was the campground that all the climbers called home when they were in the valley. It was where the serious rock jocks lived, survived on next to nothing, and climbed almost full-time. There was a two-week per year camping limit. It was a tough rule to enforce because the rangers never knew the date a camper actually arrived. When asked, the person would stretch the truth, saying they’d only been there a few days. But, when the same faces were seen in the coffee shop or campground time after time, the rangers had no choice but to do something. The climbers then had to find clever ways to avoid the rangers so they could extend their stay without getting busted. The rangers were being pressured by the Curry Company to control the rule breakers. Sometimes they’d leave for a few days, or camp behind the boulders, and quietly sneak back into camp. Most of the rangers were cool. Some were not. But, that was the case with any troop of officials. Serious enforcement would always begin in late May when the weather got nicer, the climbers were preparing for big climbs, and more tourists were visiting.

The last time I had been in the valley floor was senior ditch day in 1966. The third graduating class of Grace M. Davis High School had taken two busloads of soon-to-be graduates from Modesto to Yosemite. We hiked and rode bikes, laughed and sweated, teased and flirted. By the time we loaded back onto the buses, we were pleasantly exhausted. Compared to the trip going in, the trip going out was achingly quiet.

Like Jack Kerouac and Gary Snyder, I had come to the mountains for healing. Kerouac had written in The Dharma Bums that he had taken his wounds to the wilderness for a cure. I was seeking the same.

I was confused. And concerned. Violence wasn't the answer. It never was, or would be. But, things had to change. Guys I had grown up with were getting shot, messed up, or dying in Vietnam. My best friends and my generation were being clubbed in the streets for waging peaceful protest – for doing what our country was founded on and known for. Freedom. Democracy. Individualism.

I wanted to speak with someone who also came to the mountains to seek solace, inspiration, and guidance. Another valley refugee; a fellow Modestan. His name was Royal Robbins. He was perhaps the world's greatest rock climber. He had made first ascents of many of the big wall routes in Yosemite, including Half Dome and El Capitan. He was a true believer in clean climbing. He disliked using bolts and pitons. When he wasn't climbing, he sold paint in Modesto. I had first met him when some high school friends took me climbing our junior year of high school. Bill Magruder, John Decker, and Dave Threlfall had fallen under the spell of granite. Magruder more than the other two. Decker preferred caving and Threlfall was a skilled amateur photographer. I hadn't enjoyed the climbing. It was hard work and scary. But, I did like the evening gathering of the rock-climbing clan. There was wine, weed, and good conversation. That's where I'd first met Royal and his wife, Liz.

That Saturday evening, I knew they'd be among the boulders at Camp 4, philosophizing and solving the world's problems. I wasn't disappointed. The “dirtbags,” as they now affectionately referred to themselves after being called that by so many rangers and tourists, were huddled around a campfire. Someone was playing a guitar. A few were singing. Another group was passing around a doobie. Others were sipping Teton Tea from tin cups. Teton Tea was a mixture of tea, lemons, sugar, and port. As Royal once said, “it kept us awake and relaxed at the same time.”

I found Royal and Liz away from the group. I approached, gestured to sit, and Royal nodded. After I got comfortable on the rock, he stuck out his hand.

“It has been a while, Mikey,” he said.

“I wasn't sure you'd remember me.”

“When you pull someone off a rock wall after they've frozen, you don't forget them.”

“That was not a good day. Sorry about that.”

“Happens all the time,” Liz said, also extending her hand. “You weren't his first,” she smiled. We shook hands. Liz offered a cup of Teton Tea. I shook my head.

“Have you returned to see who's tougher, you or the rock?” he asked.

“No, I'm done with climbing and caving and all that other lunatic stuff. I want to be on flat ground and out where I can see the sun.”

“Level-headed and practical,” Liz said.

“I’m here because I need to clear my head. Think some things through. I wanted to get away from it all for a while.”

“It's good to do that on a regular basis,” Liz added.

“People who need that usually have some things on their mind,” Royal said.

“Maybe I will take a hit of that,” I said, pointing at the tea. Liz passed the cup over and I took a drink. It tasted good for bad wine. “It's the war. And the draft,” I continued. “I've got some friends who’re thinking about doing something stupid. It's all a muddle.”

“I'm sorry to hear that,” he said. “I did my time in the service. It was good for me. It's not good for everyone. I'm not a 'my country right or wrong, love it or leave it' patriot. I don't believe in this war. We're in it for the wrong reasons. We're not hearing the whole story. I know how the military works.”

“I feel the same way. I feel bad for the soldiers who are fighting and dying over there. They're doing their duty for the right reasons, but for the wrong people and the wrong war. Like you, I don’t believe the government is being straight with us.”

“So, what's the problem?” he asked.

“What I'm going to do about it.”

“And what's that?” Liz asked.

“I'm not going, but I don't know yet how to make that happen. I'm not religious, so the CO route isn't going to work. I don't want to leave the country. I'm not thrilled about joining the reserve, or National Guard. Cutting off a finger, or going to jail is crazy. I wish they'd end it.”

“That won’t happen right away,” Royal said.

“What things are your friends considering?” Liz asked.

“Radical stuff. SDS, Black Panther. Like that.”

“Violence,” he said.

“I'm afraid so.”

“That won't work,” he said.

“I know. That's why I've gone the non-violent route, like letters and protests, but that doesn't seem to be making a dent.”

“Maybe you're too impatient,” he said.

“Slow and steady wins the race,” Liz said.

“Think Grand Canyon,” he said. “The Colorado just kept going.”

“They'll draft me before that happens. “You don't know that for sure,” Royal said.

“I don't want to take any chances. It’s my life we’re talking about.”

“You should have faith in many of your fellow citizens, some of your leaders, most of the rest of the world. They know it's wrong and they will end it,” he said.

“The clock is ticking,” I answered.

“Keep doing what you're doing,” Royal continued. “A critical mass of public opinion will be reached. As Martin Luther King, Jr. said, ‘The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.’”

“If it's inevitable, why do anything?” I asked.

“It becomes preordained by the weight of our work. It's not a chemistry experiment that needs to remain undisturbed. Peace is not a Sunday walk in the park. We need to get our hands dirty to make sure that arc doesn't straighten out, or bend in the wrong direction,” he went on.

“I’m curious,” Liz said. “If you’re worried, and you obviously are, why haven’t you made a decision? Why haven’t you done something, anything, already?”

“Inertia. Fear of making the wrong mistake.”

“I understand that,” Royal answered. “It’s so much easier to stay as we are, even if it’s hurting us. Right up until it hurts too much. People don’t change unless it’s too painful to stay the same. It seems like some people don’t do the right thing until all other options are exhausted.

“For me, there are no options. There’s a right way to do something and there are all the others. Right is right.”

“I’m not you,” I said. “I wish I were that certain.”

“Nobody is,” Liz observed.

“Think of it this way,” he replied. “Remember the fable, ‘The Tortoise and the Hare?’”

“Sure. Read it as a kid. Heard it any time anybody wanted to make a point about the race going to the slow and steady versus the fast and careless.”

I glanced at Liz. She smiled.

“That’s the point,” he said. “We all arrive at the same destination eventually, whether we’re the tortoise or the hare.”

“Sure. Like that butthead who tailgates and whips around me to get wherever he’s going faster than everyone and we end up sitting side-by-side at the next light.”

“Exactly. Different people travel through life at different speeds and on different paths. One isn’t better than another, just different.”

“Well, I need to take more time to figure things out. I like to have all the information before I decide. If it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing right.”

“If you are uncompromising in your commitment to do what is right, you will die well,” Royal said.

“Slow and steady,” Liz repeated.

“I’ll get there eventually,” I said. “And know it for the first time,” Royal added.

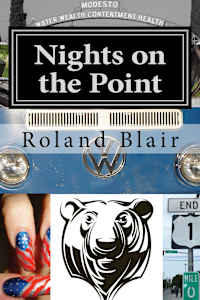

Nights on the Point

"Jack and Weston"

This time, he told himself, it would be different. This time the road would keep them honest.

They had never known the abyss, these fellow travelers. Their lives had been terminally safe, in spite of momentary descents into insanity. Which is what they were indulging when they first met. Costumed as carnies in a wicked roadshow that swept through the backwaters of the southwest and California. Weston was doing his writer thing, immersing himself in life and taking down notes. Jack was riding the two-backed beast so he could troubadour about it. Nikki signed on the first time in Sparks, tiring of a stint as a fandango dealer, being wallpaper for horny eyes. Weston and Jack were passing through on one of their sojourns to the desert, seeking signs and ancient runes. Weston went for the weather and the splendid isolation. Jack went in search of his history and in remembrance of things past.

Weston didn't waste time these days looking over his shoulder. He'd done his time living in the rearview mirror. He'd lost a wife there and didn't intend to die there again.

Prowling the as-yet-unsettled-in rooms of his new home in the flatlands, he paused to consider the reflection thrown back at him by the mirror. Staring, who did he see? The man there. A do-gooder? A vicaro? It was fashionable to care again. So, was this going to be just another arms-length experience like the wetlands piece, written from a safe distance, lashing out at everything and really doing nothing about anything? A rim shot in the dark meant to mean something? Or, was it, after all, the loneliness that was driving him with his eyes closed.

"Be good and you will be lonesome,

Be lonesome and you will be free."

The words of the Parrothead pirate wearing a white sport coat and a pink crustacean rolled around his head, taunting him, challenging him. If you want to be alone, you'll be alone. Stop feeling sorry for yourself. Shit or get off the pot. Enough said.

Weston always used music to mark out the times of his life. He remembered exactly who he was and what he was doing each time he heard a familiar melody or lyric. Just one more reason he and Jack seemed joined at the hip. And now it was time to test that joint again.

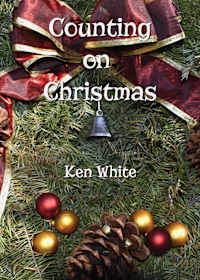

Counting on Christmas

"Ghosts"

"Can we do this again next year, Aunt Jess?" Taylor asks.

"If the fates allow," she replies.

"Awesome!" Ethan adds.

In the far corner of the room, a shimmering tableau appears.

It is Mrs. Claus, the Limping Boy, the Homeless Girl, Dudley, and George Bailey. They smile and wave, then disappear.

"It really is the most wonderful time of the year," Jessica says quietly to herself.

She finds her guitar leaning in the corner.

"This is a new one," she announces to her family. "It’s called 'Counting on Christmas.'"

She sings her newest song.

The smiling faces of her family fill the room with peace, love, and happiness.

In the end, Christmas wasn't the only thing I could count on to make me happy. It was family. The one thing we take for granted when it's the one thing we should treasure most.

At the end of the song, the tiny bell ornament on the tree swings to and fro with a silvery tinkle.

Jessica goes to find out what caused it to ring.

She peers closely at the ornament.

Reflected in its lustrous surface, she sees a sad woman about her own age standing on the bridge above Dry Creek, staring into the water.

Outside on the walkway leading to the house, all the luminarias are upright and burning brightly. The colorful Christmas lights fringing the house glow merrily. Through the large picture window stenciled with frosty Christmas images, the Christmas tree sparkles amid the joyous chaos. It resembles the last scene in the movie, Holiday Inn.

Jessica rejoins the circle of family and friends.

The courthouse clock chimes the midnight hour.

A full winter’s moon hangs high in the night sky.

A ring circles the bright moon.

It begins to rain.

The Flatland Chronicles

"The Bicyclist"

You never saw him without his bike. At the park, going to the bowling alley or pinball palace, on the streets, at the hospital, or back home to his mother's house alongside Pike Park. It's how he got from Point A to Point B. In a town of 30,000, it was practical. We all thought he was an odd duck. Of course, he couldn't drive because the cleft palate had made him mean and angry and anti-social. But, he earned our grudging respect with his athleticism. He was a natural. He could have played baseball, football, or run track. Except for the cleft palate.

You never saw him without his bike. Carrying groceries home in the chrome basket, smoking a cigarette at a political rally in the park, going to a movie downtown, or back home to the house where his high school friend was raised and now lived and offered sanctuary. It's how he got around. In a town of 150,000, it was hard, but not impossible. We all thought he was strange. Of course, he couldn't drive because he had done too many drugs and had too many DUIs. But, we put up with him because he was our classmate. Plus, he was funny. He could have done stand-up. Except for the addictions and the damage done.

You never saw him without his bike. Tipping his hat to the dogs and the whores on 9th Street, delivering groceries to the seniors at Ralston Tower, handing out clean needles to the junkies in Tower Park, swaying to the beat of MoBand, or living in his tent down by the river. It was how he got from here to there and back again. In a town of over 200,000, it was dangerous riding a bike. Nobody paid attention. Nobody thought a bicyclist had the right of way. Nobody cared. We all thought he was crazy nuts. Of course, he couldn't drive because something had happened in the Iraqi desert when he was protecting our freedom. There was no "there" there anymore. But, we accepted him because of his kindness. He could have been a saint. Except for the scars, visible and not.

In a world driven by expectations, they had none. They took things as they came and made the best of them; the sad and bad situations. They lived in the moment. Right here, right now. And they were never disappointed.

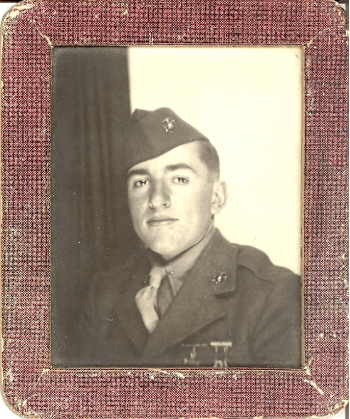

"The Hunter"

The sun was high. He was sweating. When the rabbit hopped into his row and stopped, he put the shotgun to his shoulder and fired. When the blue haze and thunder cleared, he raced to where it lay. He nudged it with his tennis shoe. It was dead.

That was the last time he ever shot a living thing.

That night, his father, who had joined the Marines as a 17-year-old, told him, "I'll drive you to Canada tomorrow."

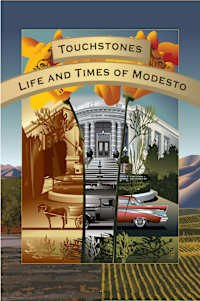

Touchstones: Life and Times of Modesto

"Introduction"

When it comes to the place where we live and work, there are many touchstones used to determine the quality of life. These benchmarks are the focus of Touchstones: Life and Times of Modesto, commissioned by the McHenry Museum & Historical Society to commemorate Modesto as it approaches the 150th anniversary of its founding.

Located in the heart of California’s Central Valley, there is more to Modesto than meets the eye. The closer you look, the more interesting it becomes. That is the story we tell in Touchstones. Our goal is to highlight the many uncommon threads that make up this amazing tapestry we call home.

Touchstones is a contemporary snapshot of the values, people, places, organizations, and activities that make Modesto a unique, attractive, and authentic California city; that contribute to its identity and quality of life and form the foundation of our community.

Touchstones is a prestigious portrait of all the things that make Modesto quintessentially Californian, as well as the cultural and economic center of Stanislaus County. This collection of essays, illustrations, stories, photographs, and artwork captures the vibrant lifestyle, rich heritage, distinctive culture, evolving diversity, and essential character of our hometown. It showcases what connects and unites us. It identifies what we’ve done, are doing, will do, and still need to do. It is a chronicle of the immediate future.

Touchstones features a special sponsored section entitled “Sharing the Heritage,” which profiles prominent local businesses and institutions that have played a major role in the growth and development of our city. These tributes look at the history, accomplishments, and vision of the many respected and diverse companies, organizations, and families born and based in Modesto. Each profile provides an opportunity for these entities to share their heritage, pride, and success, while creating a lasting legacy for future generations to enjoy.

Touchstones is much more than another history book, as it reaches into our past, present, and future to tell a memorable story about this town. Each chapter covers an important aspect of our hometown; significant themes that help illuminate our ever-transforming city. Each chapter was written by experts in their respective fields; a prestigious group of knowledgeable, well-known, and well-respected contributors.

Acclaimed author Joan Didion, a native daughter of the Golden State, once wrote that "a place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it, loves it so radically that he remakes it in his own image." We believe that. The Central Valley belongs to us and Modesto is ours.

This valley after the storms can be beautiful beyond the telling,

Though our city-folk scorn it, cursing heat in the summer and drabness

in winter,

And flee it – Yosemite and the sea.

They seek splendor, who would touch them must stun them;

The nerve that is dying needs thunder to rouse it.

I in the vineyard, in green-time and dead-time, come to it dearly,

And take nature neither freaked nor amazing,

But the secret shining, the soft indeterminate wonder.

I watch it morning and noon, the unutterable sundowns;

And love as the leaf does the bough.

This poem was written by William Everson, “the Beat Friar.” Another Central Valley patriot and refugee, he too loved this valley. It was his touchstone, not a flat spot on the map viewed in the rear-view mirror while on the way to someplace else. Unfortunately, many of us have lost our connection with this place; with what helped make us who we are, in all its kaleidoscopic glory. The familiar sight of the sun low on the flat horizon. The soft sound of whispering oak trees. The cool touch of flowing rivers. The sweet taste of a fresh peach. The memory-etching smell of irrigated soil. Here in this part of the world, we are all linked by the land, the people, and this place we call home. It is our tap root. From it, we draw sustenance, inspiration, and determination.

Our town is known around the globe. Our landmarks are universally recognized. Our products are sold across the planet. Our people have changed the world. There is much to be proud of in our community. Much to feature. Much to remember. Much to celebrate. And much to prove that Modesto is, and will remain, a great place to live and work.

It is our deepest and most sincere wish that this book will help change how we are perceived. That it will help communicate all that is singular about our little town. That it will cultivate hope for the future. A message of compassion, inclusion, trust, and optimism. And, ultimately, a sense of community.